By Tripp Mickle and Asa Fitch

A meeting between Tim Cook and Steve Mollenkopf a year ago at

Apple Inc.'s headquarters started with a tense moment.

The feuding leaders of two smartphone industry titans -- Apple

and Qualcomm Inc. -- were there to discuss a long-simmering patent

dispute. Mr. Mollenkopf, who suspected Apple of supporting a

hostile takeover of his company, initially didn't speak, leaving

his general counsel to start talking, according to people familiar

with the meeting.

The awkwardness punctuated a distant relationship between the

chief executives that has turned their companies' conflict into one

of the ugliest corporate battles in history.

Apple has called Qualcomm a monopoly and said Mr. Mollenkopf has

lied about settlement talks between the companies. Qualcomm has

accused Apple of deceiving regulators around the world and stealing

software to help a rival chip maker.

For two years, the companies have bickered over the royalties

Apple pays to Qualcomm for its patents. Discord between the CEOs,

who bring different management styles and principles to the table,

has deepened the divide. They have dug into their positions as the

dispute has escalated.

The feud heads toward a showdown this coming week, when Apple's

patent lawsuit against Qualcomm is set to go to trial -- with both

CEOs expected to testify in a case where billions of dollars are at

stake. Unless a settlement is reached, opening arguments are

scheduled to begin Tuesday in a San Diego federal court.

Close relationships between CEOs have been critical to resolving

some big corporate feuds. Former Microsoft Corp. Chief Executive

Steve Ballmer spoke weekly with Sun Microsystems Inc. Chief

Executive Scott McNealy for more than six months before the

companies settled a two-year-old antitrust suit in 2004. Mr.

Mollenkopf's predecessor, Paul Jacobs, met often with Nokia Corp.

chief Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo in the midst of their wide-ranging

patent war before they struck a 15-year agreement in 2008.

"The CEO has the ability to make decisions and understand

tradeoffs that are difficult to delegate down to others," said John

Chambers, the CEO at Cisco Systems Inc. from 1995 to 2015, who once

resolved a trademark dispute with former Apple CEO Steve Jobs. "You

pick up the phone and make a phone call or ask for a meeting. It's

based upon trust."

Messrs. Cook and Mollenkopf are so entrenched in their competing

positions -- and have so little personal connection -- that Apple's

top executives have said they don't think it's possible to cut a

deal with Qualcomm while Mr. Mollenkopf is CEO, a person familiar

with their thinking said. "It's personal. I don't see anybody who

can bridge this gap," this person said.

The two men haven't made any headway in cultivating a

relationship, people familiar with the dispute said.

Apple and Qualcomm declined to make Messrs. Cook and Mollenkopf

available for interviews.

Mr. Mollenkopf, who was born in Baltimore, is a military buff

who interned for the Central Intelligence Agency before joining

Qualcomm. He has often made decisions after consulting individually

with his top lieutenants, but many have left over the years,

leaving him isolated and reliant on counsel from outside

advisers.

Mr. Cook, an Alabama native, is an operations whiz who works to

build consensus among Apple's top-dozen leaders, often asking them,

"What is the right thing to do?" The group-decision approach has

resulted in a team of enforcers who defend Mr. Cook's view that

Qualcomm's licensing practices -- taking a 5% share of most of the

sales price of an iPhone -- was just plain wrong, allowing the chip

maker to profit off Apple innovations in display and camera

technology.

Mr. Cook's conviction on that point and his frustration over Mr.

Mollenkopf's handling of the dispute have compelled him to testify

against Qualcomm, according to people familiar with his thinking --

a rarity in his time as CEO.

A jury could determine who is the real victim: Qualcomm, which

claims Apple is violating its patents by withholding royalties, or

Apple, which argues Qualcomm has been overcharging for those

patents for years. At stake is the future of Qualcomm's licensing

model and billions of dollars in royalties that Apple will pay or

keep.

The companies have spent millions of dollars on legal fees in

hopes of gaining an edge and forcing their opponent to settle.

Since Apple sued Qualcomm in January 2017 over what the iPhone

maker considered to be unfair licensing practices, Qualcomm has

shed more than 25% of its market value, now around $68.9 billion.

The hobbled company fended off a hostile takeover by rival Broadcom

Inc. last year, and then faced the ire of shareholders who voted

against the board at the annual meeting in a show of displeasure

after the company rebuffed Broadcom.

Apple has faced bans on the sale of some iPhones in China and

Germany after courts there found it infringed on Qualcomm patents.

Its most recent iPhones now exclusively feature modem chips from

Intel Corp., a company that has lagged Qualcomm in wireless

features. This year's iPhones won't have Qualcomm's new 5G chips,

potentially putting Apple a year behind rivals like Samsung

Electronics Co. in offering speedier wireless devices.

Dow Jones & Co., publisher of The Wall Street Journal, has a

commercial agreement to supply news through Apple services.

Members of both sides say the lines of communication remain

open, though largely unused, and a settlement could be reached. The

companies are awaiting a ruling from a federal judge in an

antitrust case brought by the Federal Trade Commission against

Qualcomm that could weaken or strengthen the chip maker's

position.

Apple once needed Qualcomm, which had pioneered an efficient

system for transmitting phone calls and data. Before it could

launch the iPhone in 2007, Apple had to license Qualcomm's patents

in phone technology. Qualcomm was licensing those patents to other

cellphone manufacturers for a royalty of 5% on the price of each

handset, a fee that could equal $12 to $20 per device.

Qualcomm's terms baffled Mr. Cook, then chief operating officer.

He knew the first iPhone would carry a high price tag -- predicated

partly on Apple's brand cachet -- and didn't think Qualcomm should

get such a big share of that, people familiar with the negotiations

said. His team had proposed paying $1.50, according to court

transcripts.

Mr. Jobs, however, felt that companies should be fairly

compensated for their innovations. He had a business relationship

with Mr. Jacobs, Qualcomm's CEO at the time, speaking often. They

helped forge an agreement for Apple to pay Qualcomm a lower royalty

rate of $7.50 for each phone, according to people familiar with the

negotiations.

In 2011, Apple extended that agreement and deepened its

relationship with Qualcomm by making it the exclusive provider of

modem chips for iPhones.

As part of the terms, Qualcomm would pay $1 billion to Apple in

what Mr. Mollenkopf called incentive payments, with a stipulation:

Apple would have to pay back that money if the iPhone maker added

another chip supplier. The one-time payment was later updated to be

annual.

Both companies raked in sales. By the end of 2012 -- five years

after its launch -- Apple had sold more than 250 million iPhones

and generated more than $150 billion in sales. Qualcomm had

collected more than $23 billion in royalties from all its partners

and almost $42 billion in chip and other product sales over the

same period.

Mr. Cook, who succeeded Mr. Jobs as CEO in 2011, found it

egregious that Apple paid Qualcomm more than every other iPhone

licensee combined, people familiar with the negotiations said.

Making matters worse, he and his top operations lieutenant, Jeff

Williams, who has a longstanding relationship with Mr. Mollenkopf,

felt trapped into using Qualcomm as an exclusive modem

provider.

"We had a gun to our head," Mr. Williams said of the deal during

recent court testimony.

Mr. Mollenkopf saw it differently. Apple had made overtures

about the exclusivity deal, he said in court testimony. Messrs.

Cook and Williams promised a surge in chip sales and an advantage

over competitors by having Qualcomm chips inside millions of

iPhones, and had requested $1 billion for the privilege, he

said.

Apple confronted Qualcomm publicly over its licensing practices

in 2016. During a hearing in a case brought against Qualcomm by the

South Korean Fair Trade Commission, an Apple representative gave a

presentation on the company's "Views on Qualcomm's Abuse of

Dominance" and said Apple had yet to add another modem chip

supplier because of "Qualcomm's exclusionary conduct," according to

court filings.

Mr. Mollenkopf and other Qualcomm executives were livid,

according to people familiar with the events. They knew that behind

the scenes, Apple was producing iPhone 7 devices in China with

modem chips from rival Intel. Those devices would be revealed

within weeks of the testimony.

At Mr. Mollenkopf's direction, according to people familiar with

the events, Qualcomm began withholding the roughly $1 billion in

royalty rebates and incentives it paid Apple on the grounds that

the iPhone maker had violated its contract by misleading

regulators.

"That was a nuclear move," said a person familiar with the

events.

Apple retaliated by cutting off billions in royalties to

Qualcomm and filing its lawsuit against the chip supplier in

January 2017.

The lawsuit landed as the smartphone's salad days were ending.

Handset shipments declined for the first time in 2017, pressuring

both Apple's and Qualcomm's businesses.

Echoing a similar legal strategy Qualcomm had used with Nokia in

the mid-2000s, Mr. Mollenkopf endorsed suing Apple over patent

infringement in the U.S., China and Germany. Qualcomm began

withholding software code that Apple needed to test modem chips for

future iPhones because of its suspicion Apple shared some software

with rival Intel, something Intel and Apple have denied.

Around October 2017 Apple began designing iPhones and iPads that

jettisoned Qualcomm components.

Shortly after, Broadcom made its unsolicited takeover offer of

$105 billion for Qualcomm. The timing of the offer stirred

suspicion inside Qualcomm that Apple was supportive of the bid,

according to people familiar with the events.

After the takeover failed, Mr. Mollenkopf held hope that Apple

would come to the table to negotiate a settlement, according to

people familiar with the events. Mr. Cook was due to be deposed in

summer 2018, and Qualcomm executives thought the Apple chief would

settle to avoid speaking about his secretive company's business

practices.

Mr. Cook, however, was committed to fundamentally changing

Qualcomm's business model and sat down for his deposition last

summer without issue, according to a person familiar with his

thinking.

In the face of Apple's resistance, Qualcomm escalated a

public-relations effort to bring it to the table. The company

worked with Definers Public Affairs, an opposition research firm

based in Washington, D.C., according to people familiar with the

firm's work. The New York Times reported in November that the firm

maintained a relationship with news-aggregation website NTK

Network, which ran one article calling Apple Silicon Valley's

biggest bully and another saying Apple needed to "make nice with

Qualcomm, or offer slower, inferior products to consumers."

Meanwhile, Mr. Mollenkopf doubled down on assertions the parties

were close to a settlement. He told CNBC during an appearance that

they were on the "doorstep" of a resolution. Weeks later, Qualcomm

scored legal victories in China and Germany.

In January, an agitated Mr. Cook stated the companies weren't in

negotiations. During a CNBC appearance with Jim Cramer, he

described Qualcomm's licensing practices as illegal and said they

hadn't held talks since September. He also castigated the chip

maker for paying Definers to write fake news. "This is stuff that

should be beneath companies," Mr. Cook said.

Mr. Mollenkopf continues to believe Apple will negotiate a

settlement just as Nokia did, people familiar with the events

said.

Mr. Cook has shown no indication he is willing to bend. Apple

has pushed ahead with an effort to develop its own modem chip,

which would further reduce its dependency on Qualcomm.

For Mr. Mollenkopf, the prospect of cutting a deal that lowers

its licensing fees is risky. Qualcomm has a clause in its contracts

with other manufacturers that would require it to extend them the

same terms, potentially crushing its lucrative licensing

business.

Not cutting a deal quickly has left Apple without access to

Qualcomm's market-leading 5G chips, putting the iPhone a step

behind its Android-based competitors in the race for the next big

advance in wireless.

"Both sides have their hammers out," one person said. "There has

to be something that happens to make one side put their hammer

away."

Write to Tripp Mickle at Tripp.Mickle@wsj.com and Asa Fitch at

asa.fitch@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 13, 2019 00:14 ET (04:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

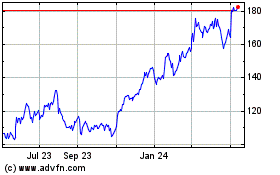

QUALCOMM (NASDAQ:QCOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

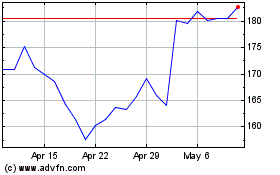

QUALCOMM (NASDAQ:QCOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024