Why Fewer Chips Say 'Made in the U.S.A.'

04 November 2020 - 1:26AM

Dow Jones News

By Asa Fitch and Luis Santiago

In 1990, the U.S. and Europe produced more than three-quarters

of the world's semiconductors. Now, they produce less than a

quarter. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China have risen to squeeze

out the U.S. and Europe. And China is on pace to become the world's

largest chip producer by 2030.

The epicenter of chip production shifted partly because

governments outside the U.S. offered often hefty financial

incentives for factory construction to build up domestic

industries. Chip companies also have been attracted by growing

networks of suppliers outside of the U.S., and an expanding

workforce of skilled engineers capable of operating expensive

manufacturing machinery.

While manufacturing has left the U.S. in recent decades, many of

the world's largest chip companies are still U.S.-based. Intel

Corp., the largest American chip company by sales, does much of its

manufacturing in the U.S., although it too has opened factories in

places like Ireland, Israel and China. Other big U.S. chip

companies, though, contract out all their manufacturing to Asian

producers such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. Nvidia

Corp., for example, which is based in Santa Clara, Calif., and is

America's biggest semiconductor company by market value, has its

chips made largely outside the U.S. As of 2019, the share of

semiconductor sales by U.S.-based companies was around 47%.

The growth of contract manufacturers like TSMC, the largest and

most advanced of its kind, have helped speed the shift of

chip-making outside the U.S. South Korea's Samsung Electronics Co.

is another big player in the contract chip-making business, and

most of its factories aren't in the U.S. The raw materials that go

into chip-making, including industrial chemicals and silicon

crystals, also largely come from outside the U.S.

The U.S. has kept a larger slice of the industrial pie in some

other fields of chip-making -- especially in ubiquitous software

tools used to design the layout of chip circuitry.

The flight of high-tech manufacturing from the U.S. has been a

theme for decades as supply chains and factories in Asia developed,

taking advantage not just of government handouts but cheaper labor

and less regulation. That exodus is particularly pronounced in

computing hardware and consumer electronics, compared with other

high-profile manufacturing sectors.

If things continue on their current trajectory, the U.S.'s share

of chip-making is expected to shrink further in coming years, in

part because China's capacity is increasing quickly.

This trend has caused concern in Washington as the U.S.'s

technological rivalry with Beijing heats up. China is pouring tens

of billions of dollars into its chip industry, hoping to eventually

match or surpass other countries.

Chips are increasingly being viewed across the globe as a

national-security priority because of the powerful role they play

not only in consumer technology but in militaries and cyberwarfare.

The U.S. has placed new restrictions on China's industry in recent

years, including blacklisting Chinese telecom giant Huawei

Technologies Co. and preventing some Chinese chip-makers from

buying American manufacturing equipment without a license.

The coronavirus pandemic has given further impetus to a U.S.

push to bring more of the chip-making industry back to American

soil. Factory shutdowns because of the health crisis disrupted

supply chains in Asia, fueling concern that the industry's

concentration there could impact U.S. access to a critical

technology during times of crisis.

Analysts say U.S. government incentives could help to reverse

that trend. A top chip-making factory -- the kind that makes

central processing units that go into computers -- can easily cost

more than $30 billion to build and operate for 10 years, analysts

estimate. So financial assistance to defray some of those costs can

change the calculus on whether to invest or not.

The U.S. historically hasn't offered federal incentives to

chip-making, although states do provide a variety of enticements

for factory-building, including subsidized land and tax breaks. In

Asia, by contrast, countries typically offer free or cheap land,

and give more help with purchasing manufacturing equipment that

accounts for most of the cost of chip-making.

Write to Asa Fitch at asa.fitch@wsj.com and Luis Santiago at

luis.santiago@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 03, 2020 09:11 ET (14:11 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

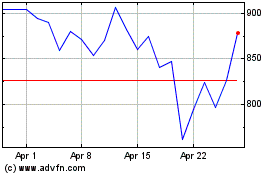

NVIDIA (NASDAQ:NVDA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

NVIDIA (NASDAQ:NVDA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024