By Rolfe Winkler

Susan Baker volunteered for Johnson & Johnson's vaccine

trial to seek protection from Covid-19. For the same reason, she

may drop out of the study.

The nurse practitioner at a North Carolina hospital has treated

Covid-19 patients. She takes care of people at high risk, including

dialysis patients and her husband and father, both of whom have

medical conditions. If she catches the virus and spreads it to

anyone vulnerable, "I don't know if I could forgive myself," she

said.

That is why Ms. Baker may drop out of J&J's vaccine trial.

She took an antibody test indicating she received a placebo instead

of the actual vaccine in the study. With positive early results for

vaccines from Pfizer Inc. and Moderna Inc. pointing toward use in

the U.S. possibly within weeks, she wants to be first in line to

get one, though she previously agreed to stick with the study so it

could fully vet J&J's injection.

"Anything that could potentially protect you, you want so

desperately right now," the 42-year-old said.

Authorization of the most advanced vaccine candidates would mark

a turning point in the fight against Covid-19. Yet it might also

set back the effort, compromising ongoing vaccine trials, including

Pfizer's and Moderna's, by prompting volunteers to quit.

Researchers scheduled two-year trials for the leading vaccines.

They didn't plan to tell the volunteers whether they got a shot or

placebo until a study ends. Subjects agreed to the terms upon

signing up.

Yet Ms. Baker and others say it is unfair to deny them vaccines

once they become available.

She and more than 100 other vaccine-study subjects recently

wrote the U.S. Food and Drug Administration asking it to encourage

companies to tell them if they got a placebo and are eligible for

an authorized vaccine.

The subjects are free to leave their trials at any time,

drug-research experts say. Yet early departures could undermine the

studies by hindering the collection of data needed to fully assess

how safe the inoculations are and how long they protect against the

virus.

"Frankly, people should not have gone into this study who didn't

feel they could wait," said Arnold Monto, a University of Michigan

health researcher who heads the panel of experts that will advise

the FDA about authorizing Covid-19 vaccines.

Dr. Monto expressed hope the issue would be rendered moot

because many volunteers who received a placebo aren't likely to be

eligible for scarce vaccine supplies for some time.

The dilemma strikes at a larger, more enduring problem with

medical testing: Many trial participants volunteer for a chance at

early access to a Covid-19 vaccine, not to further science. Yet

researchers conduct the studies to determine whether they can

recommend an experimental treatment to the broader community.

"The small group on the placebo wants access [to a vaccine] at

the time of authorization; the whole world wants more rigorous

safety and efficacy data, which means keeping people on a placebo,"

said Jennifer Miller, a Yale University bioethicist.

An exodus of volunteers in earlier stages of testing could delay

access to shots that may prove more effective, easier to deliver or

less expensive, said Marc Lipsitch, professor of epidemiology at

Harvard University.

"If we stop a few months in, we're in some sense wasting the

altruistic act of those people who volunteer in the first place,"

argued Mr. Lipsitch. "We get a fraction of the data we could get if

we could continue it."

Frederick Feit, who volunteered for Pfizer's vaccine trial and

thinks he got a placebo, said he would leave the study as soon as

he can to get the shot because that was his purpose for enrolling.

"It was never altruistic," said Dr. Feit, a 72-year-old

cardiologist at NYU Langone Health.

About 48 Covid-19 vaccines are being tested in people, according

to the World Health Organization, studies that researchers designed

to assess whether the shots safely protect against the disease. To

make that assessment, volunteers are randomly given either the

experimental vaccine or a placebo. Neither the volunteers nor

researchers know who got which.

After a sufficient number of subjects develop Covid-19,

researchers take a look to see how many of the volunteers were on a

placebo. The vaccine provides protection if fewer vaccinated

subjects fell sick.

Given the urgent need, researchers will assess whether shots

work safely weeks after study subjects get inoculated. Pfizer and

its partner BioNTech SE, as well as Moderna, have said their

vaccines were roughly 95% effective and appeared safe. AstraZeneca

PLC said its shot was 62% to 90% effective, depending on

dosage.

Data for vaccine candidates from Johnson & Johnson and

Novavax Inc. are expected in the coming months.

The rapid readouts compared with the longer testing schedules of

most vaccine development in the past should help accelerate the

approval and availability of the inoculations. It will also,

however, make it more difficult to answer important questions,

including whether there are any long-term side effects and the

duration of protection provided by the shots.

Better data also would help doctors and health authorities allay

the fears of some Americans reluctant to take a Covid-19 vaccine,

researchers say.

As companies release data from their late-stage vaccine trials

and the leading candidates move closer to authorization, some study

subjects have taken antibody tests to see whether they got the

vaccine or placebo. If it appears they took a placebo, some

volunteers have begun clamoring for access to a vaccine.

"These companies were smart enough to recruit high-risk people

into their studies. Those are the same people who are going to say

'I'm out of here, I'm going to go get something to protect myself'"

when a vaccine becomes available, said Amy Warren, 48, a nurse

practitioner in Kansas City, Mo., who is in a Moderna trial and

signed the letter volunteers sent to the FDA.

Johnson & Johnson last month sought guidance on the matter

from the committee of independent experts advising the FDA on

vaccines. J&J expressed concern that clearance of the first

vaccine would compromise other companies' ability to recruit

volunteers for their own studies, and make it harder to keep

volunteers enrolled if they are eligible for the first vaccine.

Pfizer, however, wrote in its own comment letter that it has an

ethical responsibility to inform trial volunteers if a vaccine was

approved and to provide it to placebo recipients. The company told

study subjects this month that it is exploring how to give the

vaccine to these volunteers but needs regulators to approve.

Marion Gruber, director of the FDA's Center for Biologics

Evaluation and Research, said during a recent panel appearance that

the agency is talking with vaccine makers about how to achieve the

goal of data collection while also making vaccines available to

those who need them most.

Meanwhile, in the U.K., regulators sent a bulletin to Covid-19

vaccine study subjects there this month saying they would be

contacted if a vaccine is cleared, and told if they got the placebo

and are eligible to receive the real shot.

--Jared S. Hopkins and Jenny Strasburg contributed to this

article.

Write to Rolfe Winkler at rolfe.winkler@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 27, 2020 09:14 ET (14:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

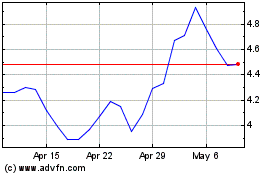

Novavax (NASDAQ:NVAX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

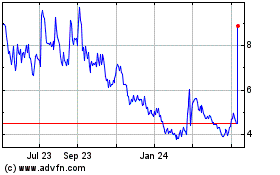

Novavax (NASDAQ:NVAX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024