By Sebastian Herrera and David Benoit

Amazon.com Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Berkshire Hathaway

Inc. set out three years ago to join and transform health care.

Instead, they struggled to solve even fundamental challenges, such

as understanding what some kinds of care actually cost.

Haven, the joint venture they set up together in 2018 to use

technology and find new ways to reduce costs for their combined 1.5

million employees, will end operations next month. The project cost

the three companies roughly $100 million combined, people familiar

with its budget said.

From its inception, Haven faced challenges obtaining data, staff

turnover, fuzzy goals and unexpected competition, according to

current and former employees and executives at Haven and the

partner companies. Those factors doomed the partnership from early

on, those people said.

Data was a central challenge. Haven struggled to aggregate and

analyze information on health-care costs for the three companies'

employees. Data concerns from the partners and resistance from

insurers stymied Haven's efforts to determine how much the

companies paid for medical care and why, the people said.

Haven isn't the first venture to struggle with the lack of

transparency in health-care costs and data, an issue that has long

complicated government reform efforts and technology solutions. A

new Trump administration rule, effective this year, is supposed to

force greater disclosure of the rates negotiated between hospitals

and insurers.

As of Jan. 1, hospitals are required to publish the prices

negotiated privately with each payer for 300 common services for

easy use by consumers and make public the same information for all

their procedures in a format that can be read and analyzed by

computers.

"You can't solve the problem when you can't see it," one of the

people involved in the venture said. "We were all doing our own

thing and health care was too big a problem for us to solve."

A Haven spokeswoman said the founding companies "were committed

and engaged from day one through to the decision to end Haven's

operations" and will continue to collaborate informally.

While leaders of the founding companies were initially

optimistic about Haven's potential, the challenge of applying its

work across three sprawling corporations slowed progress and added

complexity, the people close to the venture said. Eventually, the

companies realized they could implement many projects more

efficiently on their own, they said.

Despite Amazon, JPMorgan and Berkshire's collective size, they

lacked scale to garner enough negotiating power with care

providers. To achieve their big aims, they would have needed more

partner companies to join, or cooperation with government, said

health-care specialists familiar with Haven's work.

"They did not have enough bargaining power with the insurance

industry or with providers," said Lyndean Brick, CEO of health-care

consulting firm Advis. Sweeping changes "will take massive

governmental and business reform, and we have yet to see that

cooperation."

Haven, which had about 75 employees at its peak, took on more

projects than staffers said they felt it was equipped to handle.

Much of its work had to be approved by the three founding

companies, slowing progress.

Atul Gawande, a writer, surgeon and Harvard University professor

who was tapped to lead Haven, stepped down in May, saying he

planned to focus on the Covid-19 pandemic. He didn't respond to

requests made to his press office for comment. In November, he was

named to President-elect Joe Biden's coronavirus task force.

The three founding companies showed varying interest in the

venture, the people said. JPMorgan Chief Executive Jamie Dimon, who

had come up with the venture idea, was the only CEO out of the

three companies to actively participate in meetings and help push

forward pilot projects, these people said.

Employees at Boston-based Haven found themselves working on

projects similar to ones the individual partners were also

developing, particularly with Amazon, which has focused on a number

of health-care expansions in recent years. Those include a virtual

primary care for Washington state employees and an online pharmacy

business launched in November.

About two years ago, Haven began work on a project nicknamed

"Starfield, " a virtual primary-care service geared in part toward

improving and reducing the cost of care for employees with chronic

conditions. The program would also offer employees online doctor

visits, the people said. Workers on the Haven project were caught

off guard in the fall of 2019 when Amazon publicly launched "Amazon

Care" for its Seattle employees, a telehealth service with similar

capabilities, although it focused on a broader segment of workers,

the people familiar with the matter said.

Amazon Care had been in the works before Starfield, but Haven

employees were unaware of Amazon's work until the company announced

it, people familiar with the matter said. A pilot project for

Starfield in Columbus, Ohio, involving JPMorgan employees got

underwhelming engagement, the people said. Soon after, Haven

executives began to deprioritize the project and eventually shut it

down around last May, they said. By then, the pandemic was driving

doctors to virtual visits anyway.

An Amazon spokeswoman said Amazon Care and Starfield "are

entirely separate projects and programs and do not have anything to

do with one another."

"Amazon has been working in lockstep with Haven and the founding

partners on a number of pilots and tests within our benefits

programs," she said. Beth Galetti, Amazon's senior vice president

of human resources, "was fully engaged as a member of Haven's board

and was empowered to move things forward in real time."

A spokeswoman for Berkshire acknowledged CEO Warren Buffett's

absence in Haven meetings, saying that Berkshire investment manager

and Geico CEO Todd Combs has represented the company.

Mr. Dimon told bank employees in a memo Monday that the three

companies would continue working together, just not on a formal

basis. He said Haven worked best as an "incubator" of ideas.

Dr. Gawande's departure left a leadership void that was never

filled, leading some Haven employees to leave, people familiar with

the matter said. Some staff who had joined from the founding

companies went back. Hiring slowed in 2020, and Haven had at least

one round of layoffs. The venture employs around 60, and its staff

is expected to be split among the three companies.

The companies, while powerful, were an odd fit, former staff

members and health-care experts said. Their vastly different

workforces sprawled across many locations, making it difficult to

implement health-care initiatives in an industry that is largely

dependent on local providers. Amazon's workforce includes not just

corporate employees but hundreds of thousands of warehouse workers,

while Berkshire Hathaway has a swath of subsidiaries.

"Many aspects of health care are local, and [employees] were

spread around at somewhat different levels of these organizations,

and that makes it much harder" to accomplish health-care

initiatives, according to Kimberly MacPherson, co-director for the

Center for Health Technology at the University of California,

Berkeley.

Data-sharing provided some of the thorniest challenges,

according to people familiar with its struggles. Initially, the

leaders of the joint venture imagined that if they could see what

the three companies were spending on health care and why, the data

would show them what to fix, those people said.

Getting a hold of those figures proved difficult. Haven

employees built a platform to allow them to compile cost and claims

data from all three companies, but the companies were unhappy with

how it worked, people familiar with the matter said. Due to those

concerns, Haven had to rebuild aspects of the system, further

delaying the goal of understanding, analyzing and reducing costs,

the people said.

Haven also struggled to access information that insurers

typically keep secret, such as granular details behind the pricing

and cost structures of certain types of medical procedures, people

familiar with these challenges said. Such details are often

required to be kept confidential under contracts between insurers

and hospitals.

--Anna Wilde Mathews and Dana Mattioli contributed to this

article.

Write to Sebastian Herrera at Sebastian.Herrera@wsj.com and

David Benoit at david.benoit@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 07, 2021 12:26 ET (17:26 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

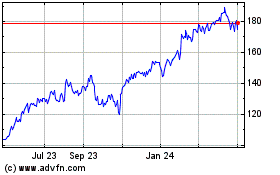

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

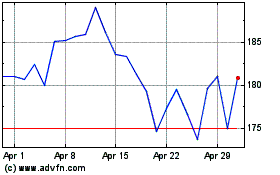

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024