By Jean Eaglesham and Nina Trentmann

After its business was hit by the pandemic, retailer Ulta Beauty

Inc. appears to have used some accounting cosmetics to add a gloss

to its financial results.

Operating income at the once-fast-growing chain, which

temporarily closed stores during the health crisis, plummeted to

$13 million for the nine months through October, a fraction of the

$613 million earned in the same period in 2019. Two

coronavirus-related items affected the math: a $40 million

impairment charge for the value of some stores that reduced the

operating income, and $51 million of federal tax credits that

increased it.

Ulta also reported a much healthier $98 million "adjusted

operating income." This tally, designed to strip out one-time

items, added back the $40 million impairment cost, which boosted

the adjusted number, but didn't take off the $51 million of federal

aid. If that aid had been removed, the adjusted-operating-income

number would have been half of what the company reported.

About a year into the pandemic, regulators are ramping up their

scrutiny of potentially misleading coronavirus disclosures by

companies. A senior Securities and Exchange Commission official

warned in December that companies should be consistent in positive

and negative adjustments when showing the impact of the

pandemic.

An Ulta Beauty spokeswoman denied cherry-picking data to flatter

the adjusted metric. She said the impairment cost was a legitimate

one-time charge caused by the impact of Covid-19 on some stores,

not a direct cost of the pandemic such as cleaning supplies.

An SEC spokeswoman declined to comment.

About one in three companies put a dollar amount related to the

impact of the coronavirus in their earnings for the quarter that

ended in December, according to a review of 199 filings from

S&P 500 companies by data provider Calcbench. The financial

pain inflicted includes everything from reduced revenues to

increased bad debts, impaired assets and restructuring costs. On

the plus side, several companies reported savings on travel and

trade-show expenses, the review found.

While metrics that don't follow generally accepted accounting

principles, or GAAP, have been criticized, they can be used to help

investors disentangle the financial effect of what companies

consider a one-time event from the performance of the underlying

business.

American Airlines Group Inc. racked up an $8.9 billion net loss

last year and a non-GAAP net loss excluding special items that --

unusually for this measure -- came in even wider at $9.5

billion.

Like Ulta, the airline added back into its adjusted metric

coronavirus costs, in this case some $3 billion, and federal

pandemic aid, which totaled about $4 billion.

The SEC doesn't dictate how companies report coronavirus costs

and income. But the agency says companies must ensure comments on

the effects of the pandemic are accurate and not misleading.

Restaurant chain Cheesecake Factory Inc. agreed in December to

pay $125,000 to resolve SEC civil charges it misled investors last

spring by saying its locations could continue to operate, when it

estimated it only had about four months' worth of cash left. A

spokeswoman for Cheesecake Factory, which didn't admit the SEC's

findings in its settlement, declined to comment.

One area of Covid-19 accounting that the SEC said it would

scrutinize closely is any changes to revenue to compensate for

losses because of the health crisis.

Uber Technologies Inc. spent tens of millions of dollars last

year to help its drivers and others affected by the pandemic. The

ride-hailing company added back this coronavirus cost in an

adjusted-net-revenue figure, boosting the number. As the company

had always done, however, the adjustment also stripped out a

measure called excess driver commissions, leaving the adjusted $8

billion tally for the nine months through September lower than the

$8.9 billion GAAP revenue figure.

Uber stopped quoting an adjusted net revenue in fourth-quarter

and full-year results earlier this month. An Uber spokesman

declined to comment.

Another bugbear of regulators and investors is companies that

exclude one-time coronavirus costs quarter after quarter, or try in

other ways to use the pandemic as cover to remove some regular

expenses from their non-GAAP numbers.

David Knutson, vice chair of the Credit Roundtable, which

represents institutional investors, said the longer the pandemic

continues, the harder it will become for companies to single out

one-time costs and effects caused by Covid-19. "I think there will

be a fraction of companies still clinging to this excuse," Mr.

Knutson said, adding that companies should be used to operating

under Covid-19 by now.

The SEC in December questioned Puerto Rico-based Oriental Bank

over an adjusted-net-income measure that stripped out "additional

provision for credit losses due to Covid-19." The agency asked in a

letter to Oriental's owner, OFG Bancorp, how it was differentiating

expected credit losses caused by the pandemic from other credit

losses.

OFG agreed in its response to drop the metric and the SEC closed

its review, the filings show. A spokesman for OFG declined to

comment.

Many companies aren't putting dollar numbers on the pandemic's

impact, an analysis of earnings shows.

Roughly one-quarter of S&P 500 companies last year reported

an adjusted figure for earnings before interest, tax, depreciation

and amortization, or Ebitda. But only about one in 10 of those

companies disclosed adjusted Ebitda because of Covid-19 during the

three quarters through December 2020, according to data provider

MyLogIQ.

Jay Knight, a member of law firm Bass Berry & Sims PLC and

former SEC counsel, said it isn't surprising so few companies are

doing coronavirus adjustments "just because it's so difficult to

quantify some of these items."

Another possible reason: Many companies might not feel under

shareholder pressure to dress up the impact of the coronavirus by

using alternative numbers. Earnings have broadly held up well and

most stocks are up. In contrast to hits to profits that might be

the company's fault, executives generally don't need to explain

away the effects of the health crisis.

The SEC is pushing for companies that exclude pandemic-related

expenses to provide details to investors.

Private prison company CoreCivic Inc. in its earnings for the

quarter through September excluded "expenses associated with

Covid-19" from a non-GAAP measure, without explaining what those

expenses were.

When the SEC in December wrote asking for details, CoreCivic

broke down the Covid-19 costs into six separate categories, ranging

from what it called "hero bonuses" of $500 each for employees to

the added cost of giving prisoners food in disposable containers so

the inmates wouldn't need to congregate in cafeterias. The SEC

closed its review, the filings show.

A CoreCivic spokeswoman said in a written statement that the

expenses all fell within the SEC"s guidance for non-GAAP Covid

adjustments.

Write to Jean Eaglesham at jean.eaglesham@wsj.com and Nina

Trentmann at Nina.Trentmann@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 23, 2021 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

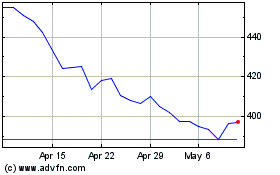

Ulta Beauty (NASDAQ:ULTA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

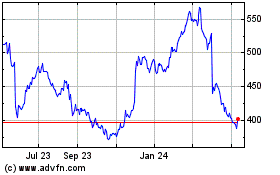

Ulta Beauty (NASDAQ:ULTA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024