Prices for the vital industrial minerals known as rare earths

appear to have moderated in recent weeks following two years of

relentless gains, as the supply outlook brightens and dominant

producer China faces possible legal challenges to export

restrictions.

Rare earths, which is shorthand for a collection of 17 minerals

used to make products from hybrid-car batteries and oil-refining

agents to military equipment, have been surging with prices of some

rising more than tenfold since 2009 amid panic buying. China

controls almost the entire global supply, and its export limits,

mine restructurings and other policies have sparked a frantic

scramble to secure the obscure metals.

Determining prices for rare earths is tricky because the market

for them is illiquid and only small quantities are produced

globally. Some of the biggest buyers and sellers complain that they

have little clarity on pricing.

But Australia's Lynas Corp., which publishes references related

to what it expects to produce at its Mount Weld deposit in the

state of Western Australia, says prices for lanthanum, often used

to make catalysts for refineries, has dropped to $92 per kilogram

as of Sept. 19 from $135.02 in the second quarter. Prices for

cerium, sometimes used in glass, have also dropped to $92 per

kilogram from $138.29 in the second quarter, Lynas says.

On Tuesday, a J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. analyst cited falling

rare-earth prices as a reason to slash his outlook for

Colorado-based Molycorp Inc., a rare-earths producer often

considered an industry bellwether. Its New York Stock

Exchange-listed shares subsequently tumbled nearly 22%.The shares

rose 1.4% to $42.03 in midday trading Wednesday.

Molycorp officials couldn't be reached Wednesday for comment. In

an interview earlier this month, Molycorp Chief Executive Mark

Smith said he has seen signs of "demand destruction" for rare

earths, as companies take steps to reduce their rare-earths use,

such as glass makers recycling cerium. But, expressing confidence

in prices underpinned by Chinese policy, he said, "I go back to the

supply-demand relationship in this industry."

Rare-earth prices remain far above where they were just two

years ago. Lanthanum, for instance, still hovers 18 times above its

2009 price, while prices for cerium are still nearly 25 times

higher, according to Lynas. Indeed, some international prices

haven't fallen at all, in particular those that are known as heavy

rare earths, like terbium, which is used in advanced lasers and

optics.

Still, some industry observers see reason to hope for an end to

what has been constantly climbing prices. "As a general rule,

people think prices are going to drop," says Luther C. Kissam,

chief executive of Albemarle Corp., a Louisiana maker of specialty

chemicals that imports Chinese lanthanum.

Companies are looking for ways to reduce their rare-earth use,

taking some pressure off demand. Manufacturers and industrial

companies such as W.R. Grace & Co. say they have found ways to

reduce the rare-earth content of their products.

Also, Grace said last November that, due to China's rare-earth

export crimps and surging prices, it would charge customers of its

fluid catalytic cracking catalysts a surcharge that it didn't

specify. In subsequent filings, including its 2010 annual report,

Grace cited "the cost of and availability" of rare earths among its

risks. For the first half of 2011, it reported $47.8 million in

accounts receivable and inventories in the period relating to rare

earths.

"We expect that rare earth market conditions could change

quickly, and they remain an uncertainty for the foreseeable

future," Grace said in the half-yearly report last month. But Grace

also said it was developing catalytic products with low or no rare

earth content, and it said many customers were receptive. Company

officials declined to comment.

Still others have moved production to China, freeing them from

China's export restrictions. Hitachi Ltd. is considering moving

some production of high-grade magnets to China, among many other

options, said one executive of the Japanese company.

"Generally speaking, it's wise for a company's management to

keep all options open," the executive said.

Trade lawyers, meanwhile, predict the legality of China's policy

to allocate supplies to foreigners using government quotas will

shortly be undermined by an unrelated, but similar, case being

considered by the World Trade Organization involving a separate

class of minerals. "This is a short-sighted and self-defeating

policy by China," said James Bacchus, global chairman of law firm

Greenberg Traurig LLC and a former chief WTO judge.

China has said it is tightening export limits on rare earths

because processing them takes a toll on the environment. Beijing

says it doesn't want to remain the world's near-monopoly

producer.

A much-watched mineral now is neodymium, an ingredient in

permanent magnets that are used in wind turbines and hybrid cars.

China's largest producer of rare earths this week announced price

supports for it, which could further encourage industry to locate

in the country. Lynas says the price of neodymium has been flat

since midyear on international markets at around $265 per kilogram

but has dipped in China.

It isn't clear whether the pause will last. Given the "wild

card" of Chinese policy, volatile pricing is here to stay,

according to Edward Richardson, vice president of specialized

Indiana magnet maker Thomas & Skinner Inc.

"Without dependable and consistent data, we are left with

stories, anecdotes and perceptions," he said in an email.

-Norihiko Shirouzu in Beijing contributed to this article.

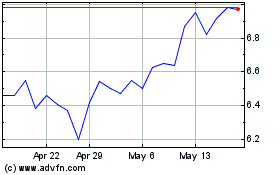

Lynas Rare Earths (ASX:LYC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2024 to Jan 2025

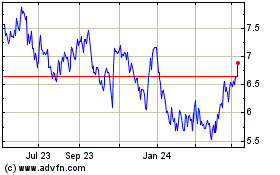

Lynas Rare Earths (ASX:LYC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2024 to Jan 2025