Puerto Rico's debt crisis moved into a more treacherous phase

for residents, lawmakers and bondholders Monday, with the expected

default by the Government Development Bank on a $422 million

payment.

The likely missed payment, the largest so far by the island, is

widely viewed on Wall Street as foreshadowing additional defaults

this summer, when more than $2 billion in bills are due.

Together with the spread of the dangerous Zika virus, the risk

of cascading defaults is putting new urgency on delicate bipartisan

negotiations in Washington over legislation granting new powers to

restructure more than $70 billion in debt issued by the

territory.

Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew warned on Monday that a U.S.

"taxpayer-funded bailout may become the only legislative course

available" if Congress doesn't approve the proposed restructuring

legislation. The warning came in a letter sent to Congress.

The island's debt is held by mutual funds, hedge funds, bond

insurers and individual investors, who were attracted in part by

tax benefits and high yields. Any GDB default Monday would cast

serious doubt on the commonwealth's ability to make other future

payments, which "means that other defaults are very likely on other

Puerto Rico credits," said Paul Mansour of the investment

management firm Conning.

The government will make a $22 million interest payment due

Monday, a GDB spokeswoman said, but it will likely miss a $367

million principal payment. The government earlier swapped $33

million worth of debt coming due Monday for new debt with later

maturities, the spokeswoman said.

A provisional deal announced Monday with hedge funds holding

about $900 million of GDB bonds shows the complex lengths that

Puerto Rico's leaders must go to as they wait for Congress to

establish a legal framework for a broader restructuring. Under the

proposed swap, bondholders would swap into new GDB bonds worth

about 57% of their original claims, but would exchange that debt

yet again, and take a bigger haircut, if the island achieves a

global restructuring

Monday's developments amount to the latest sign that a

long-running economic crisis has reached an acute stage, embroiling

financial markets and the U.S. political process. Benchmark Puerto

Rican bond prices fell to near record lows Monday, with some

investors paying less than 65 cents on the dollar for general

obligation bonds maturing in 2035. Just two years ago, investors

snapped up $3.5 billion of those bonds, which carry an interest

rate of 8%. Prices dropped below 64 cents on the dollar only once,

when Puerto Rico passed a law last month allowing the suspension of

debt payments.

While Monday's default had been expected, the missed payment

creates new headaches for the local government. Its agencies

maintain their bank accounts at the GDB, which serves as the

government's fiscal agent and financial adviser and backs loans to

private enterprises, so the default could trigger litigation to

freeze those accounts. The government had already passed

legislation to limit withdrawals from the agency to avoid a

potential bank run, and the commonwealth's treasurer last month

began opening accounts at private banks.

Puerto Rican Gov. Alejandro Garcí a Padilla had said in a

televised address Sunday that the island was struggling to pay for

such basic goods as fuel for police cars.

"We simply don't have enough money to pay for all these services

and pay our creditors," he said.

The default could also mark a turning point after weeks of

negotiations on Capitol Hill. House Republicans are completing

legislation to create a federal oversight board with the power to

sign off on local budgets and to authorize a court-supervised debt

restructuring. The bill wouldn't commit U.S. taxpayer funds, but

some creditors have described it as a bailout because they say it

might violate existing contracts.

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R., Wis.) has forcefully rallied

Republicans to back the legislation, the product of unusually

bipartisan discussions with the Treasury Department. Mr. Ryan is

warning colleagues that, if the local government can't manage the

crisis, calls for actual taxpayer assistance will mount.

"The longer this goes on, the more likely there will have to be

a federal bailout," said Marc Joffe, a former senior director at

Moody's Investors Service who is now principal consultant at Public

Sector Credit Solution, a research group.

Mr. Garcí a Padilla hasn't said what he would do if Congress

doesn't agree on legislation. He denounced a multimillion-dollar

lobbying effort against the bill, backed by various creditors, as a

"brutal campaign of racial discrimination and lies," and he said

failure by Congress to address the crisis "could become a public

embarrassment for the United States."

Puerto Rico, whose residents are U.S. citizens, has been mired

in recession for a decade and borrowed heavily to balance budgets.

Despite the shaky economy, investors snapped up its debt for years

thanks to generous tax incentives. The borrowing spree, however,

did little to create economic opportunity on the island, and

residents have steadily left for employment on the U.S. mainland,

eroding Puerto Rico's tax base.

More recently, the Zika virus is threatening to strain the

island's public health infrastructure while damaging its tourist

sector. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported

last week the first U.S. death related to the Zika virus, that of a

Puerto Rican man in his 70s who died in late February.

Puerto Rico's debt crisis isn't seen as likely to spill into the

U.S. economy or the broader $3.7 trillion municipal bond market

because the island's unique set of economic troubles make it

something of an outlier.

Congress is considering legislation because the commonwealth's

public institutions don't have access to federal bankruptcy courts,

unlike municipalities in U.S. states. Because Puerto Rico isn't a

country, it can't turn to the International Monetary Fund for

assistance.

Despite weeks of close negotiations, the Treasury hasn't blessed

the bill. Officials say restructuring provisions can't allow

creditors to drag their feet in any workout. Conservative

Republicans, meanwhile, are seeking assurances that the legislation

wouldn't set a precedent for distressed states, for example, to

write down debt in order to shore up public pensions.

The battle in Congress boils down to one about leverage.

Treasury and Puerto Rico want a process that makes it easier to

restructure debts because this will give the island's financial

advisers more leverage in negotiations with bondholders. Creditors

want one that makes it impossible to restructure debts or void

contracts because this preserves their leverage.

Mr. Ryan is caught in the middle. As bondholder advocates lobby

against the bill, he risks losing Republicans. This would force him

to choose whether to push through a bill with predominantly

Democratic support.

Treasury says a broad restructuring regime is needed in part to

avoid litigation between creditors who hold debt with differing

security pledges and who are likely to sue each other to make

claims on the island's dwindling revenues. Creditor battles,

officials say, could prolong the debt crisis for years and chill

private investment in Puerto Rico.

Meantime, bondholders have accused the local government of

refusing to negotiate in good faith and, together with the Obama

administration, of exaggerating the crisis in order to compel

federal legislation.

Last year, the island made several debt payments only after

taking emergency measures, such as withholding tax refunds and

delaying payments to local contractors.

Write to Nick Timiraos at nick.timiraos@wsj.com, Heather Gillers

at heather.gillers@wsj.com and Matt Wirz at

matthieu.wirz@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 02, 2016 16:35 ET (20:35 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

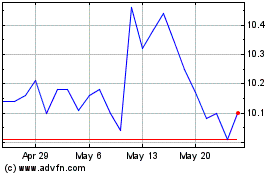

Pacific Current (ASX:PAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2024 to May 2024

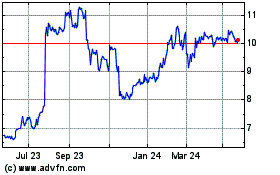

Pacific Current (ASX:PAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2023 to May 2024