By Costas Paris

Oceangoing shipping companies are keeping commerce moving around

the world as governments try to keep their staggering economies

propped up and supplies heading to increasingly strained

communities.

But many operators are going into survival mode themselves, as

the coronavirus pandemic takes a toll on trade.

"Demand is caving and supply chains are in distress," said

George Lazaridis, head of research at Greece-based Allied

Shipbroking. "Nobody knows when restrictions will be lifted and the

industry is in a battle for survival."

Moody's Investors Service sent a grim warning sign of the

troubles spreading through shipping when the firm cut the ratings

outlook for Denmark's A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S, the world's biggest

boxship operator by capacity, from stable to negative.

Many transportation operations, including port cargo handlers

and trucking companies and railroads that move goods inland, are

considered essential businesses in nations that now are locking

down business.

Unlike airlines, which could be set to gain billions of dollars

in bailout funds, most shipping companies can't count on financial

relief from governments, however. Much of the world's commercial

cargo fleet operates under a variety of flags and already enjoys

substantial tax benefits.

Many of the world's shipping companies are scrambling to adjust

to the new world.

Bulk carriers, the operators that move coal, iron ore, wheat and

other commodities, are coping with low freight rates and slipping

demand. China, the world's biggest commodities importer,

drastically cut down inbound cargoes of iron ore and coal in the

first quarter.

A recovery in freight rates isn't expected until late into the

second half and that is if the virus doesn't engulf big exporters

like Brazil and Australia. The average daily freight rate for large

bulkers stands at around $8,000 a day, less than half the

break-even level.

The specialized car carriers that haul automobiles and other

vehicles around the world are reeling as automotive factories shut

down. Norway's Wallenius Wilhelmsen, one of the world's biggest car

carriers, last week said it would furlough about 2,500 workers --

half of its production staff in the Americas -- and pulled 14 ships

from its fleet.

Only tanker operators appear to be weathering the pandemic

storm. Crude carriers are on a healthy run as oil importing

countries and traders are buying big amounts of oil to replenish

strategic reserves and for storage at record low prices.

Still, a recession in the global economy would sharply reduce

the demand for oil in the coming months.

For container ship carriers, the operators that move most of the

world's manufactured goods, the downturn is already here.

The carriers in that sector canceled about half of their

services out of China in the first quarter and are continuing to

"blank" sailings on major trade routes for the second quarter as

they try to preserve cash.

In January "we thought some cargo would be delayed, but things

would be OK as ports stayed open," said the chief executive of a

European ship chartering company with a fleet of two dozen vessels.

"Now, I have to let go of a quarter of my staff and I don't know

whether I'll still have a business at the end of April. "

"The virus in China alone led to more than 120 blank sailings.

The pandemic spread is likely to lead to substantially more blank

sailings than this," said Lars Jensen, chief executive of

Copenhagen-based SeaIntelligence Consulting. "If the 37% reduction

is an indication of a global demand shortfall, this means all

carriers are facing mortal risks."

Mr. Jensen expects overall container volumes to decline about

10% this year because of the pandemic, similar to the decline in

the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

While big operators hold ships in storage, smaller operators

have less room to ride out the crisis.

China's supply shortage put dozens of smaller shipping companies

with niche routes from China to destinations like Japan, South

Korea and the Philippines in distress, erasing their cash

flows.

Those companies have only a handful of ships apiece but they are

critical to global trade because they shuttle containers and

commodities on regional trade lanes that feed parts and finished

goods to operators on the bigger routes.

Singapore-based Pacific International Lines, the world's

10th-biggest container line by capacity, according to maritime data

provider Alphaliner, has been selling off some assets to raise

cash. The company has been seeking to stave off creditors amid a

heavy debt load.

A.P. Moller-Maersk's main Maersk Line business went into 2020

with nearly $4.8 billion in cash. But Moody's in downgrading Maersk

said that won't insulate the carrier from the factory closures and

protectionist actions spreading around the world.

"The shipping sector in general and container shipping sector in

particular are dependent on world trade and activity demand for

goods from industrial companies as well as consumers," Moody's said

in its report Tuesday.

In Germany, Alfred Hartmann, the head of the country's big

shipowners' association, warned that repayment of some shipping

loans "will turn out to be problematic."

"Our focus going forward will be costs, further deleveraging,

and [to] make sure that we keep enough cash," Rolf Habben Jansen,

chief executive of Hapag-Lloyd AG, said in a March 20 investor

conference call.

The German container line earned a $418 million net profit in

2019, but Mr. Jansen said that last year now seems "a very long

time ago."

Write to Costas Paris at costas.paris@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 02, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

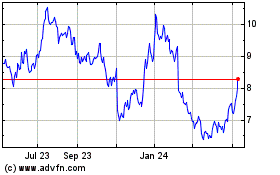

AP Moller Maersk AS (PK) (USOTC:AMKBY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2024 to Jan 2025

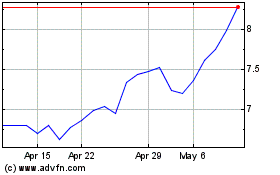

AP Moller Maersk AS (PK) (USOTC:AMKBY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2024 to Jan 2025