By Jacob Bunge

On Midwestern fields and in research greenhouses, agricultural

giants like Monsanto Co. and BASF SA are teaching machines how to

farm.

The companies are expanding early-stage investments in

artificial intelligence, joining other industries in betting that

research and decision-making can be streamlined with computer

programs that teach themselves by picking patterns out of data.

Corn plants chosen with the help of computers are growing in the

U.S. this year, and algorithms are sifting North American weather

data to anticipate crop threats such as pests and disease.

BASF, the German chemical conglomerate, is working on automated

image- recognition capabilities similar to those that confirm faces

on Facebook and Apple's Photos app. The idea is to analyze farmers'

photographs of suspicious spots on crop leaves and deliver early

warnings for diseases such as wheat leaf rust, said Richard

Trethewey, who heads bioscience digitalization for BASF.

While some farmers are skeptical of the technology, others

figure it could evaluate crop development and identify disease as

well as or better than they can. Gunter Jochum, who grows canola,

soybeans and wheat near Winnipeg, Manitoba, watched firsthand the

learning curve of a computer program developed by BASF known as

Maglis.

In the spring of last year, Mr. Jochum told Maglis the date he

sowed canola, and his fields' coordinates. The program "pretty

accurately" guessed when the first seedlings would pop up, he said,

and by harvest time it had grown smarter as it predicted when crops

would be ready for harvest and how many bushels his land would

yield.

"In the beginning, I was a little bit leery," said Mr. Jochum.

"As the season went on, I was astonished how close it was." This

summer, he said, Maglis parsed weather and field data to foretell a

damaging plant fungus.

The companies, which spend billions of dollars annually to

research new seeds and farm chemicals, declined to specify how much

of that goes toward developing artificial intelligence.

Monsanto, the world's largest seed company, has been taking

computers' advice as it matches up corn strains to produce the

highest-yielding and sturdiest varieties.

Eight years ago, data scientists at the St. Louis company used

15 years' worth of information on corn varieties to build a

self-teaching algorithm. That has helped Monsanto researchers more

accurately predict how thousands of combinations of strains will

perform in their first year in the field.

Michael Graham, who heads Monsanto's plant-breeding operations,

said the system lets the company evaluate about five times more

corn varieties than it could in the past, and save a year of

research time. Over the past year, Monsanto has sold corn seeds

matched with the algorithm's input to U.S. farmers.

Self-learning software doesn't yet range freely across farm

fields. Mr. Graham said the technology's shortcomings showed up one

year when Goss's wilt, a disease that withers corn leaves, struck

further east in the U.S. corn belt than it had in the past,

catching Monsanto's corn-breeding model off guard. At BASF, the

Maglis machine learning functions remain under human supervision,

with crop specialists reviewing its analyses.

The field-by-field variation in weather, soil and pest

conditions poses steep challenges for artificial-intelligence

software, even with the data-collecting abilities of high-tech

machinery and soil sensors. And many critical data points -- such

as crop yield or the ultimate impact of a dry spell -- only emerge

once per year.

As the farm sector nurtures artificial intelligence's early

promise, it is looking for ways to fuse the technology with other

advances in agriculture. Tractor maker Deere & Co. agreed this

month to pay $305 million to buy Blue River Technology, a startup

developing tractor-towed robots that can analyze crops and apply

fertilizer and pesticides plant-by-plant. In the Netherlands,

Novozymes AS is developing microbe-based products that help crops

grow faster and fend off pests.

The company aims to use machine learning to identify promising

genetic patterns in microbes' DNA sequences. Some microbes chosen

with help from machine-learning technology are now being tested in

Novozymes' greenhouses, "where we see very clear improvement in the

[success] rate we are getting," said Ejner Bech Jensen, head of

bio-ag research at the company.

Mr. Trethewey, of BASF, said machine learning could revamp the

way the company studies chemical molecules' effects on fungus,

weeds and other pests. BASF is developing artificial intelligence

that can snap photos of test plants growing in petri dishes, using

visual-interpretation technology to track the effects of

herbicides. The technique frees lab workers from repetitive tasks

and avoids human error, he said.

BASF, which sold $5.9 billion worth of pesticides and other

agricultural products last year, is powering its push into

artificial intelligence with a new supercomputer named Quriosity,

now being installed at the company's headquarters in Ludwigshafen,

Germany.

While agricultural giants explore machine learning, many farmers

don't expect to abandon traditional methods anytime soon.

Dale Huss, who oversees artichoke production for

California-based Ocean Mist Farms, said that any technology that

can help farming is worth considering. "But the day's not going to

come when something tells me what seed to plant, how much to water,

or what type of fertilizer to use, " he said.

Mr. Jochum, the farmer near Winnipeg, sees room on his farm for

artificial intelligence and may even pay for the advice that Maglis

provides. Still, "nothing really beats the human touch right in the

field," Mr. Jochum said. "And a machine is only as good as the

information you input into it."

Write to Jacob Bunge at jacob.bunge@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 13, 2017 07:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

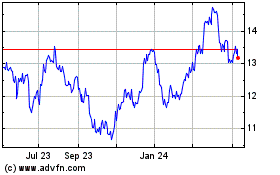

BASF (QX) (USOTC:BASFY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2024 to Jan 2025

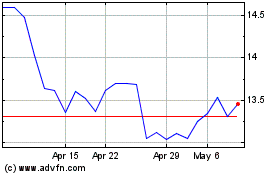

BASF (QX) (USOTC:BASFY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2024 to Jan 2025