For decades, it was one of the most politically and diplomatically fraught exchange rates, the frontier between two of the largest economies in the world.

Today, the yen/dollar relationship generates less heat than before, not least because Japan’s apparently-unstoppable economic progress looks less formidable than was the case in the late Eighties.

Back then, the authorities in Tokyo were accused of deliberately holding down the value of the yen to help propel Japan’s mighty export machine to greater triumphs in world markets. Now, that is an accusation more often levelled at China with relation to its currency, the yuan.

“Downward pressure has intensified”

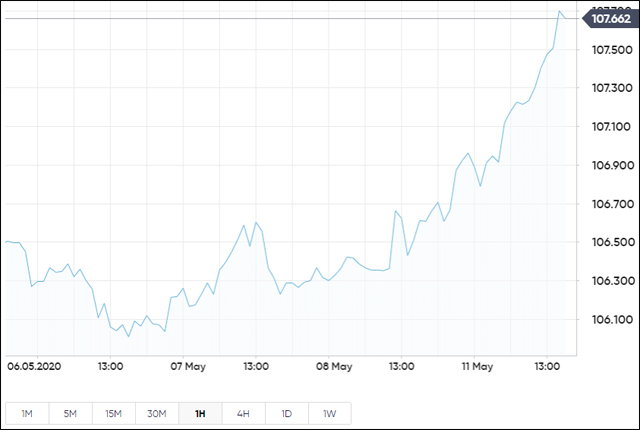

This morning, the dollar was 0.49% higher, buying 107.209 yen. One month ago, a dollar could buy 107.753 yen on 13 April, and three months ago, on 11 February, a dollar was worth 109.787 yen.

One year back, on 13 May 2019, the dollar bought 109.305 yen.

US Dollar/Japanese Yen

The dollar’s softening is related to the rapidly deteriorating economic situation in the United States, with unemployment soaring at a record rate as a result of measurers to try to control the Covid-19 epidemic. But, as the Bank of Japan has made clear, the Japanese economy is also in trouble for the same reasons.

In a communique issued earlier today, the country’s central bank stated: “Downward pressure on Japan’s real economy has intensified further due to the spread of COVID-19. Although financial and capital markets have been less volatile recently, partly reflecting policy responses taken by major economies, there is a great risk that they will become unstable again with the real economy becoming depressed on a global basis. Thus, the current situation continues to warrant vigilance.”

It added: “The global economy, including Japan, has been in an increasingly severe situation, as seen in the fact that demand has either declined significantly or disappeared, excluding some exceptions such as for IT-related goods and daily necessities, and that business conditions have deteriorated further, mainly in the services industry.”

“Lost decades” blunt Japan’s economic force

Suggestions of currency manipulation started to surface in the late Sixties, with Japan and what was West Germany singled out for American disapproval. These two export-heavy economies were seen to be simultaneously hiding behind America’s defence forces while making big inroads into US domestic markets.

At times this criticism was short on logic, as when Japanese companies started buying US assets such as film studios and Rockefeller Centre in New York. An undervalued yen would have made such acquisitions harder rather than easier.

Meanwhile, Japan’s “lost decades” of the Nineties and early 2000s rendered the country’s economy less of a threat to US supremacy. At the same time, industry’s domestic costs were rising, leading to the “offshoring” of some activities to cheaper locations.

This, in turn, reduced the effectiveness of a weaker yen in terms of boosting exports, because the offshored activities would be on the wrong side of the exchange rate.

Ironically, given that it gave up its own currency 21 years ago, Germany remains the target of American ire with regard to its export focus, allegedly given an unfair helping hand by the low rate at which the German mark was absorbed into the euro.

Hot Features

Hot Features