By Scott Patterson and Alexandra Wexler

KOLWEZI, Congo -- Apple Inc., Volkswagen AG and about 20 other

global manufacturers found themselves on the defense when Amnesty

International reported two years ago that the cobalt in some of

their batteries was dug up by Congolese miners and children under

inhumane conditions. Many of the companies said they would audit

their suppliers and send teams to Congo to fix the problem.

Their efforts haven't kept hand-dug cobalt out of the industry

supply chain.

At a cobalt mine named Mutoshi in Kolwezi, freelance Congolese

workers known as creuseurs -- French for miners -- could be seen in

May descending underground without helmets, shoes or safety

equipment. The mine's owner is part of the global cobalt supply

chain for companies including Apple and VW.

Miners there were using picks, shovels and bare hands to unearth

rocks rich with the metal. Water sometimes rushes into holes and

drowns miners, and an earth mover buried one alive last year, said

local creuseurs and mine officials.

"Of course, people die," said Christian Schöppe, then acting

chief executive of the Mutoshi mine's owner, Chemaf SARL, in May.

"This is really shitty work." He called the miners "barbarians" and

said Chemaf had resisted giving them safety equipment because they

would sell it.

Global demand is soaring for cobalt, which is used to conduct

heat in lithium-ion batteries in products from smartphones to

electric vehicles. Cobalt prices have more than doubled since 2016,

putting Congo in the spotlight. The country produced 67% of the

world's cobalt in 2017, according to Darton Commodities Ltd., a

U.K.-based cobalt-trading firm.

"Selling cobalt," said Chemaf Chairman Shiraz Virji in May, "is

an easy job today."

Concerns about human-rights abuses in cobalt mining mounted

after the 2016 report documenting inhumane conditions among

creuseurs, also called "artisanal" miners. Companies have faced

backlash from consumers disturbed by the use of workers toiling in

dangerous conditions in one of the world's most impoverished

countries.

It isn't easy for global manufacturers to trace cobalt's source

in Congo, because it passes through multiple companies and

countries. Some mining operations mix industrially produced and

creuseur-dug cobalt, say mining executives who have worked in the

country.

"When we speak to companies along the battery value chain, this

is one of the biggest issues they have," said Milan Thakore, an

analyst at U.K. commodities researcher Wood Mackenzie. "How do we

trace where the cobalt has actually come from?"

The Wall Street Journal found that cobalt from Mutoshi, one of

Congo's biggest creuseur-worked mines, is still making it into the

global supply chain, although where it ultimately ends up is hard

to know.

-- Creuseurs mine Mutoshi, a barren pockmarked hilltop, and sell findings to

Chemaf.

-- Chemaf sells cobalt from Mutoshi and a mechanized mine that doesn't use

creuseurs to Swiss commodity trader Trafigura Group, the companies say.

-- Trafigura's biggest cobalt customers include Umicore NV, a Belgian

chemicals giant, Chemaf and Umicore say.

-- Samsung SDICo., a South Korean battery maker, says it buys cobalt-based

materials from Umicore and buys some cobalt directly from Trafigura.

-- Apple and VW say they buy batteries from Samsung SDI.

One company in the chain, Samsung SDI, says it is aware some of

the cobalt it gets from Chemaf is produced by the Mutoshi mine's

creuseurs. If companies stopped buying it, said Samsung SDI's

director of corporate strategic development, Bernardino Ricci, it

would put people out of work. "We're pro artisanal mining because

we don't want the communities to be affected."

'Problem for Apple'

Chemaf's Mr. Schöppe said he wasn't concerned about where his

company's creuseur-mined cobalt wound up.

"I don't care about supply-chain problems," he said in May at a

Chemaf facility in Congo. "That's a problem for Apple and Samsung."

He stepped down as CEO last month and says he remains on Chemaf's

board. His successor hasn't begun, and Mr. Schöppe says Chemaf

executives can no longer speak with journalists.

Umicore disputes any implication that it buys cobalt produced by

creuseurs at Mutoshi -- or anywhere else -- referring to its

longstanding policy against the practice. Umicore Senior Vice

President Guy Ethier said the cobalt Umicore buys from Chemaf is

produced only industrially, not by creuseurs. He said he visited

Mutoshi in August and said Umicore has methods to detect whether

creuseur-mined metal is mixed into its supply.

Umicore receives about three-fourths of the cobalt Chemaf

produces and Samsung SDI gets the rest, through Trafigura, Chemaf's

Mr. Schöppe said. He said he doesn't know if any cobalt Umicore

buys is from Mutoshi. Mr. Virji didn't respond to a question about

whether his company sells creuseur-mined cobalt to Umicore.

Trafigura, which said cobalt it buys from Chemaf includes metal

from Mutoshi, declined to say if it sells cobalt to Umicore or

Samsung. Apple representatives declined to comment on Umicore's

supply chain and didn't respond to questions about Samsung SDI's

use of cobalt from Mutoshi. An Apple spokeswoman said the company's

supplier code of conduct "underscores a commitment to human rights,

environmental protections and sound business practices."

A VW spokeswoman said the company is confident "the established

due diligence framework of Umicore makes sure that no ASM" --

artisanally-mined material -- "is entering our specific supply

chain." VW didn't respond to questions about Samsung SDI's use of

cobalt from Mutoshi.

Apple and others have also used batteries whose supply chains

trace to another big buyer of creuseur-mined cobalt in Congo,

China's Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co., the 2016 Amnesty report said.

Apple no longer uses cobalt produced by Huayou, said a person

familiar with the iPhone maker.

Huayou spokesman Bryce Lee said the company has implemented a

system to better manage its supply chain and has worked with a

nongovernmental organization to help comply with global standards

for human rights in mines.

Creuseurs in Africa

Creuseurs are ubiquitous across Africa, especially in diamond

and gold mining, where they work independently of mining companies,

sometimes on companies' land with those companies' approval,

typically without safety equipment.

In Congo, creuseurs often dig for cobalt outside designated

mining areas with no supervision and frequently bring children to

work alongside them, say some mining executives and nongovernmental

organizations. Congolese creuseurs often sell their findings at

markets to traders or directly to the mines' owners. They produce

about 20% of Congo's cobalt, according to S&P Global Market

Intelligence.

The Congolese government says it is seeking to protect the

miners, for whom the informal labor is the only option. "I cannot

lie and say that it's easy," said Richard Muyej Mangeze Mans,

governor of Lualaba province, where the Mutoshi mine lies, "but we

are making progress."

Chemaf sends mixed messages about creuseurs. Its website states

its cobalt operations are "fully mechanised," an industry euphemism

for industrial mines without creuseurs, although it also mentions a

"pilot" artisanal-mining project in Mutoshi. Thousands of creuseurs

could be seen living and working at Mutoshi in May. Chemaf's Mr.

Schöppe said he wasn't aware of the website's "fully mechanised"

claim.

"We work in bad conditions," said Fiston, a 32-year-old creuseur

at Mutoshi.

Leslie Melrose, Chemaf's general manager of mining, said in May

that it is addressing Mutoshi working conditions and plans

eventually to replace creuseurs with an industrial operation. Mr.

Virji, Chemaf's chairman, said: "We are going to make it right" for

Mutoshi workers.

Trafigura says thousands of creuseurs at Mutoshi have been

provided safety equipment, and a recent video of the site reviewed

by the Journal shows dozens of workers wearing helmets and

gloves.

Chemaf said that Mutoshi has 300,000 tons of cobalt in the

ground, enough to keep producing 30 to 40 years, and that the mine

has the capacity to produce 16,000 tons of cobalt annually. That

would make Chemaf one of the world's largest cobalt producers.

Supply-chain reviews

Companies have moved to scrutinize their cobalt sources,

including Umicore, which in 2016 hired accounting firm

PricewaterhouseCoopers to review its cobalt supply chain, including

whether it used creuseur-mined metal. Umicore's Mr. Ethier said the

company is "very concerned about human rights, child abuse, health

and safety."

PwC didn't visit Congo for its audit, according to Umicore. PwC

Partner Marc Daelman said: "Our assurance relates to validating

compliance by Umicore with their publicly disclosed framework."

VW works with battery-cell providers to analyze mines and

determine if there is "child labor or unacceptable working

conditions," said its spokeswoman, Leslie Bothge. VW is aware

Chemaf gets cobalt from industrial and artisanal sources, she said.

VW interviews nongovernment organizations and industry experts in

Congo, she said, and sends teams there to verify its standards are

met.

The Apple spokeswoman, Sam Fulton, said the company started

mapping its supply chain for rechargeable batteries in 2014 and

that 100% of its smelters participated in independent third-party

audits into cobalt-supply sources. Apple declined to say if its

audits included Chemaf. The company's supplier responsibility

standards don't exclude the use of creuseur-mined commodities.

"There are real challenges with artisanal mining of cobalt in

the Democratic Republic of Congo," an Apple spokesman said, "but we

believe deeply that walking away would do nothing to improve

conditions for people or the environment."

Apple and others have joined groups such as Better Cobalt,

Responsible Cobalt Initiative and Global Battery Alliance that are

developing methods to help trace cobalt's origin and eliminate

abuses.

Pact, the Washington, D.C., NGO that China's Huayou says it

hired, develops methods to help mining companies using creuseurs

become compliant with Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development regulations.

Ferdinand Maubrey, a project director at RCS Global, a U.K.

supply-chain-audit company overseeing the Better Cobalt project,

says: "It's not about a perfect mine site, it's about showing

what's going on at the mine site and showing continual

improvement."

Other companies are exploring cobalt deposits in the U.S.,

Canada and elsewhere. Guaranteed creuseur-free cobalt is available

from some big industrial-mining companies operating in Congo, but

much industrial production is locked up for years in long-term

contracts.

In a 2017 follow-up report, Amnesty applauded Apple's moves to

weed out child labor from its supply chain, saying it is "the

industry leader when it comes to responsible cobalt sourcing." It

said VW hadn't addressed whether certain companies in its supply

chain received cobalt from Congo.

The follow-up said: "Some of the richest and most powerful

companies are still making excuses for not investigating their

supply chains."

Chemaf and Umicore's relationship traces back decades. Mr.

Virji, Chemaf's chairman, said the pharmaceutical company he

started in Congo got a payment in the 1990s in an unusual form:

cobalt. He found a trader to sell it to Union Minière SA, a Belgian

mining company that in 2001 changed its name to Umicore.

In 2002, Congo rolled out a mining code seen as friendly to

international mining companies, and Mr. Virji said he bought

licenses to mine sites including Etoile, where creuseurs dug for

metal. Mr. Virji eventually ejected the creuseurs and built a

mechanized operation there.

Umicore began focusing on chemicals production in the early

2000s and became one of the world's biggest cobalt consumers,

including of Chemaf's production.

Mr. Virji said he bought creuseur-produced ore from licensed

traders to supplement metal his mechanized facility produced. In

2014, he said, he bought Mutoshi from Congo's state mining company

for $52 million. Mutoshi, as now, was 100% creuseur-mined, he said.

He considered evicting the creuseurs but decided instead to buy

their production as "a way to control them."

Until this year, children worked at Mutoshi alongside adults,

said Chemaf's Mr. Melrose and creuseurs there, hauling bags of

cobalt and helping women clean rocks at watering holes. Children

have been largely removed from the site, Mr. Melrose said.

Trafigura said it hired Pact to help Chemaf improve working

conditions. "Controls around the human-rights impact are being

introduced as we speak, and it's not without its problems," said

James Nicholson, head of corporate responsibility at Trafigura.

Chemaf's Mr. Schöppe said that, because the work is dangerous,

the Pact effort "doesn't change anything."

Mr. Virji, Chemaf's chairman, at his house in Congo in May, said

he was enjoying newfound success a year after nearly facing

bankruptcy, having bought a Rolls-Royce for his second home in

Dubai. He said he had plans to buy a private plane for Chemaf's

use.

"I'm treating myself," Mr. Virji said.

Write to Scott Patterson at scott.patterson@wsj.com and

Alexandra Wexler at alexandra.wexler@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 13, 2018 08:51 ET (12:51 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

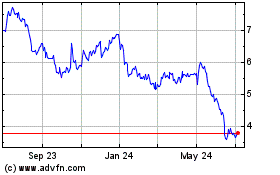

Umicore (PK) (USOTC:UMICY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2024 to Jan 2025

Umicore (PK) (USOTC:UMICY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2024 to Jan 2025